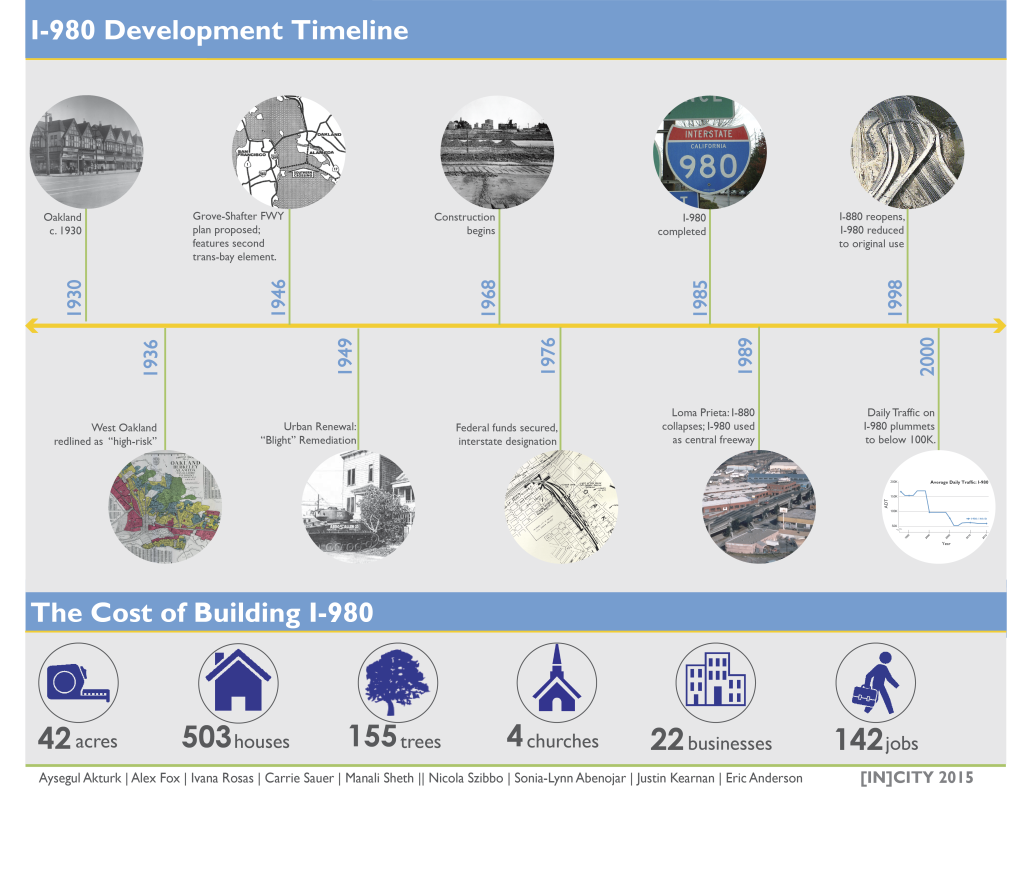

The entangled story of what is known today as the I-980 freeway spans over six decades. To tell the story of I-980 is to tell the story of Oakland’s aspirations of becoming both an integral transportation connection point for the Bay Area and a destination for commercial crowds and a growing economy.

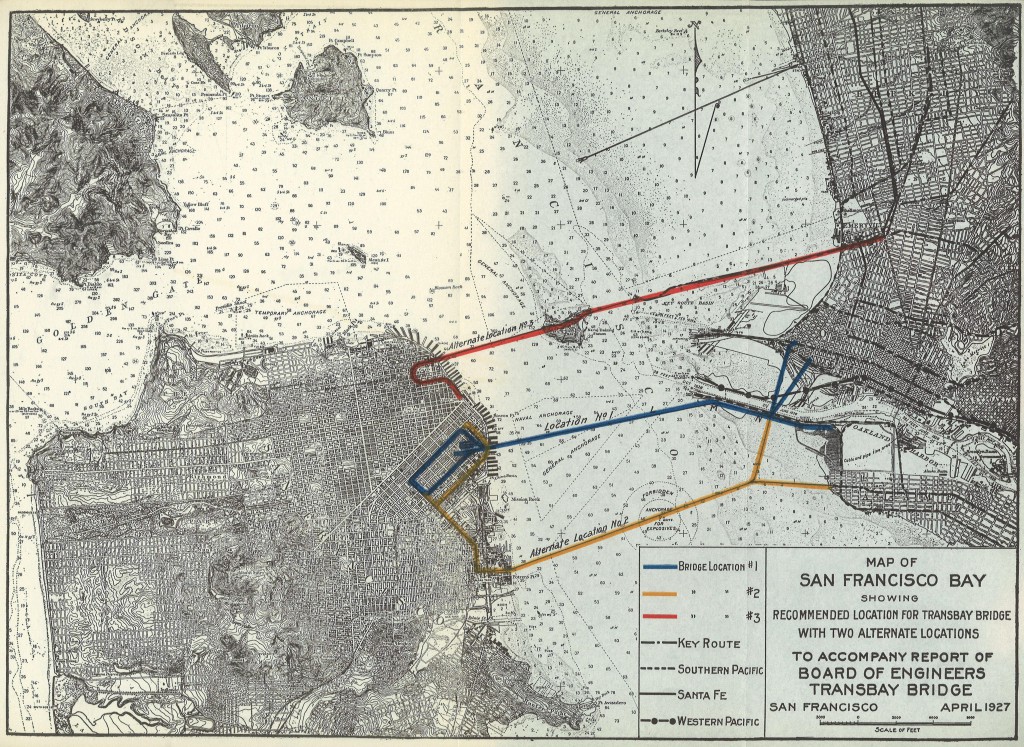

The alignment that would later result in I-980 predates the alignment of the current Bay Bridge. In this 1927 diagram a Grove-Shafter alignment is identified via Alameda in Location No. 1.

The slow train of events that would result in the destructive implementation of I-980 began in 1927 when engineers identified a number of routes for a potential San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. Although a routing through Yerba Buena Island was ultimately chosen, nearly as soon as the bridge was opened, leaders started planning a second bridge.

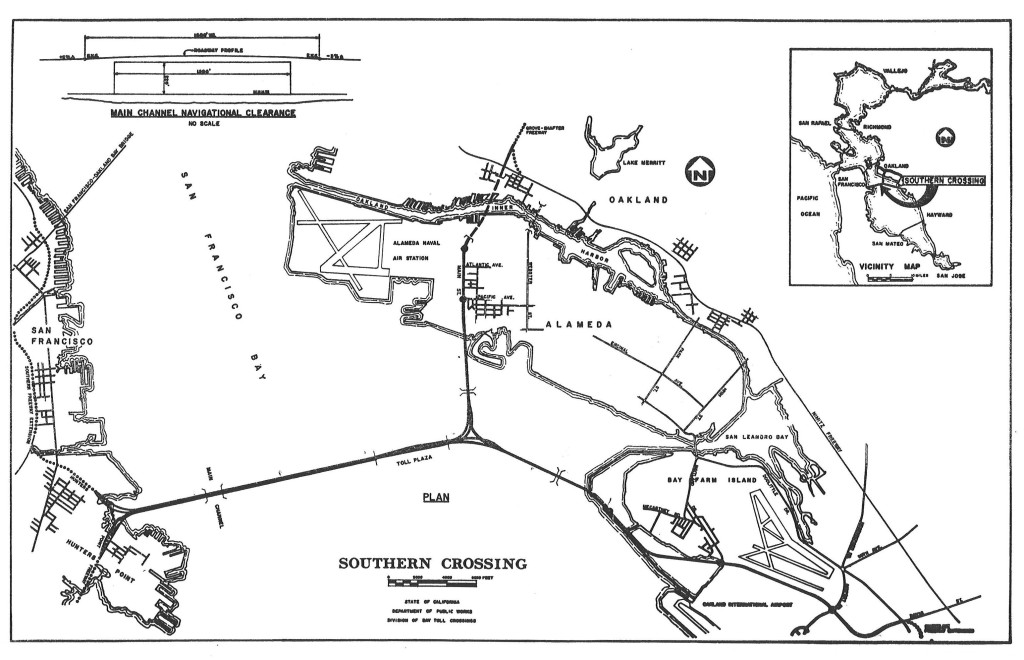

By 1948 an alignment for the Second Crossing was developed that would connect Castro Street and Grove Street in Oakland with Army Street in San Francisco. This bridge was located to connect with the Grove-Shafter Freeway that had been proposed by the Oakland City Planning Commission along with the MacArthur (I-580) and Cypress Freeway (I-880) in 1947.

The construction of the MacArthur Freeway and the Cypress Freeway, sealed off West Oakland and its primarily African-American residents from the employment base at the Port of Oakland. These freeways were allowed to cut through the low-income, predominantly African-American communities because of “blight” designations, and decision makers and planners did not see the losses that resulted from these projects as significant.

However, only the eastern part of the Grove-Shafter freeway (known today as CA-24) was initially completed to connect the Caldecott Tunnel to the MacArthur Freeway by the late 1960’s. This left but one missing link between the proposed Southern Crossing and the new highway to Contra Costa County. Despite the lack of progress, the proposed freeway haunted the neighborhood; once the lines were drawn on the map disinvestment began and the self-reinforcing spiral of blight began.

Despite resident concerns in the late 1960’s the City of Oakland jumped into the debate to advocate for the construction of I-980 in order to connect the proposed future City Center project:

The division of the opinion involved long-range hopes that downtown Oakland will be revitalized with a massive City Center project of major hotels and office towers.

A Redevelopment Agency planning official, Michael Kaplan, told city councilmen yesterday the Grove-Shafter Freeway design skirting downtown would be inadequate to serve such a future development.McCarty, backed by a State Highway Division engineer, said the proposed link could be changed in the future if the need arose and Federal Financing became possible.

…

Redevelopment Agency officials have maintained that this proposal, while serving the flanking streets adequately, fails to provide “direct service routes” to any future City Center development over “flying ramps.”

Kaplan called for further studies which he said probably would show the need for an on off-ramp system spanning local streets to connect to the freeway with garage structures in the downtown area.

–“Downtown Freeway Disputed” 1.15.1969; Oakland Tribune

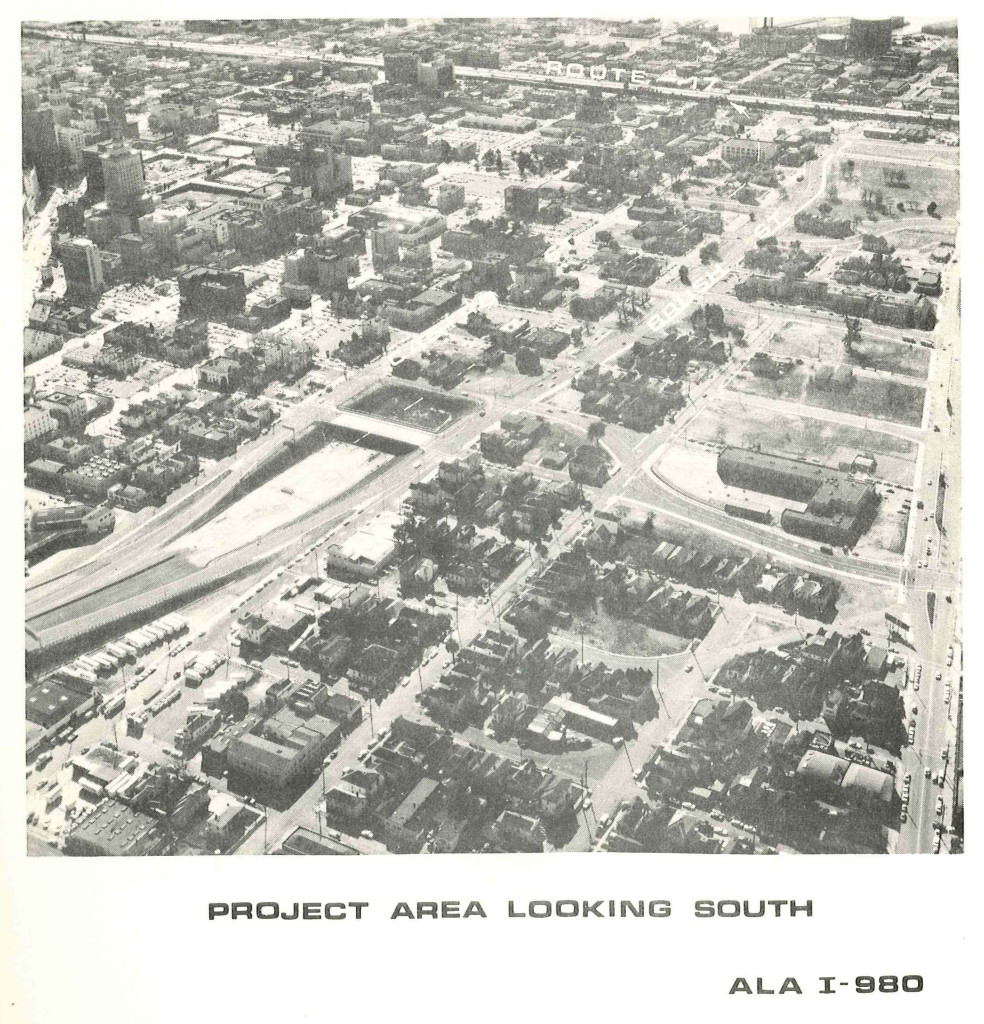

By 1971 the pieces were falling into place and regional leaders proposed a San Francisco-Oakland Southern Crossing that included a complicated interchange built in the middle of the Bay to connect a highway directly to the Oakland Airport. Yet the backlash was beginning. With bulldozers beginning to clear a path for the highway, the community rose in opposition to the downtown section of the Grove-Shafter at the same time that the Sierra Club unleashed a firestorm against the Southern Crossing proposal. Residents sued the city to demand replacement of the 503 homes slated for demolition as a condition of proceeding. For much of the 1970’s the demolition was halted and, while the prospects for a Southern Crossing Bridge became increasingly remote, the highway ended abruptly at 18th Street.

The situation changed in 1975, at the urging of the Oakland business community, then-Governor Jerry Brown ordered that the completion of the Grove-Shafter be a high priority on the condition that 50% of the construction employment and 30% of long-term City Center employment be reserved for minorities. Thus, the project was now solely justified on its necessity for the proposed City Center redevelopment, however Oakland still lacked the money to finish building the project. Eventually, despite its short 2 mile length, the project won designation as a federal highway — I-980.

Even before construction was completed in 1985, the impacts of the decision were already being felt. I-980 formed the last section of a loop of freeways that completely ensnared West Oakland with freeways. A significant portion of the challenges faced byWest Oakland in the past three decades can be attributed to the disconnection of the neighborhood from the rest of Oakland and from the deliberate municipal neglect that such separation enabled. These freeways, like many throughout the country were not constructed to serve the communities they displaced, but to create easy automobile access for suburban communities to reach the central business districts of both Oakland and San Francisco. It is particularly tragic that, to echo a protest slogan at the time, new “white freeways” were still allowed to run through “black bedrooms” two decades after the revolt against urban highways began.

Read on to learn more about the ConnectOakland concept to reconnect West Oakland…